- Government

-

-

-

Mayor James Perkins welcomes you to the Dallas County seat in the largest contiguous historic district in the State of Alabama.

The City is best known for the 1960s Selma Voting Rights Movement and the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965.

“Queen City of the Black Belt”

-

-

- Departments

- Visitors

-

-

-

Welcome to Selma, Alabama

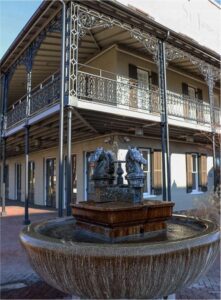

Opportunities for exploration abound in Selma and Dallas County, Alabama. Locals and visitors alike often find themselves basking in our rich layers of history and abundant recreational opportunities.

Whether you are looking for a journey through time or a relaxing getaway from the constant grind of big city life, Selma is the place for you. Come explore with us today.

-

-

-

- Doing Business

- How Do I ?

- Government

-

-

-

Mayor James Perkins welcomes you to the Dallas County seat in the largest contiguous historic district in the State of Alabama.

The City is best known for the 1960s Selma Voting Rights Movement and the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965.

“Queen City of the Black Belt”

-

-

- Departments

- Visitors

-

-

-

Welcome to Selma, Alabama

Opportunities for exploration abound in Selma and Dallas County, Alabama. Locals and visitors alike often find themselves basking in our rich layers of history and abundant recreational opportunities.

Whether you are looking for a journey through time or a relaxing getaway from the constant grind of big city life, Selma is the place for you. Come explore with us today.

-

-

-

- Doing Business

- How Do I ?